What do a 2000 year old Christian Tradition, the Anglican Lambeth Conference and English author Aldous Huxley have in common?…

In 1930, the Anglican Church made a decision that proved tragic for the entire world. About the only two voices that realized the problem were, of course, the Catholic Church, and surprisingly, an agnostic.

The year is 1932. On the Continent, Adolf Hitler is still 11 months away from gaining control of the German government. Though he continues to search for a way to gain the electoral majority necessary to rule Germany, he has already won a major victory in England, a victory that will continue to grow and metastasize long after he lies dead from a self-inflicted gunshot wound in a burning bunker in Berlin 13 years in the future.

Yet, even as English Churchmen nurture the seed of Hitler’s philosophy on their isle, another voice has risen from among the inhabitants of that gallant land. This voice has spent the last two years forming one of the most insightful and strident attacks on Nazi philosophy ever concocted, and it is now, in February, 1932, that the author releases his work into the stream of history. The battle between the philosophies continues to be fought down to this very day: the battle between the eugenics, advocated in seminal form by the Church of England, and the natural law, upheld by an agnostic who saw the preposterous conclusions to which the contraceptive philosophy must inevitably lead.

The agnostic was Aldous Huxley; his book, Brave New World, would constitute not only an incredibly prophetic description of the contracepting society, but also a deft parody of the Christian church which first legalized the idea. Prior to 1930, contraception had been uniformly condemned by every Christian denomination in the world since the death of Christ.

Unfortunately, Darwin’s work between 1854 and 1872 had a profound influence on European and American society. His “survival of the fittest” argument soon produced the idea that some human beings were less fit, less worthy to procreate than others. Both sides of the Atlantic forged ahead with applications of this “breakthrough” in scientific understanding. Scientific journals devoted to eugenics, the breeding of a better human animal, soon became common throughout Europe. Francis Galton, the man who coined the word “eugenics,” established a research fellowship in University College, London in 1908, and his Eugenics Society began work in the same year.

By the early 1920s, Margaret Sanger and several of her English lovers were touting contraception and involuntary sterilization as a way to limit the breeding of the “human weeds,” as Sanger called them: the insane, the mentally-retarded, criminals, and people with Slavic, Southern Mediterranean, Jewish, black or Catholic backgrounds (ironically, Sanger was herself raised by a Catholic mother). Though most supporters of atheistic rationalist scientific progress don’t advertise it, Hitler’s racial purity schemes were nothing more than the application of 1920s “cutting-edge” biology. When this attitude encountered Christianity, the results were uniformly explosive. Ever since 1867, Anglican bishops had been meeting roughly every ten years at Lambeth Palace, London, in order to discern how best to govern their Church. Mounting eugenics pressures had required the bishops in both the 1908 and the 1920 conferences to fiercely condemn contraception. But the constant eugenics drumbeat would not let up.

The 1930 conference brought even greater internal challenges; many of the people advising the bishops were eugenicists, indeed, at least one attendee, the Reverend Doctor D.S. Bailey, would be both a member of the International Eugenics Society and an active participant in the conference.

Between the general mood of society and the insistence of advisors, the Anglican bishops were placed under extreme pressure to allow some form of artificial contraception. On August 14, 1930, after heated debate, they voted 193 to 67, with 14 abstentions, to permit the use of contraceptives at the discretion of married couples. The decision rocked the Christian world — it was the first time any Christian Church had dared to attack the underlying foundations of the sacred marital act, the act in which another image of God was brought into creation through the parents’ participation in co-creation with God. Pope Pius XI, deeply saddened, issued Casti Connubii, just four short months later on December 31, 1930, reiterating the constant Christian teaching that artificial contraception was forbidden as an intrinsically evil act.

H.G. Wells’ stories of a scientific utopia combined with the publication of the Lambeth decision and Casti Connubii to fire Huxley’s imagination. What would a society which fully endorsed contraception look like? Though Huxley was by no means a Catholic, he possessed a keen intellect and an incisive pen.

His conclusions were soon plain — society as we understood it would fail to survive. Writing in the grand tradition of English parody, he constructed a wickedly accurate portrayal of the contraceptive society, written so as to ensure his English audience would recognize his portrayal of the Church which had set them on the road toward it. In so doing, he inadvertently created an allegory which supports Catholic teaching.

The Catholic teaching on contraception finds its basis in the book of Genesis and in sacramental theology. Adam and Eve were the original bride and bridegroom, the first married couple, their marriage a natural bond formed by God. When Adam and Eve disobeyed God and ate of the fruit of the tree, Adam compounded his sin by publicly repudiating Eve, saying to God, “The woman whom THOU gavest to be with me, she gave me fruit of the tree, and I ate” (Gen. 3:12).

The first couple’s twin sins of disobedience and failure to own up to their actions brought twin curses upon them: increased pain in childbirth and increased toil in order to bring forth sustenance from the earth. Because Adam’s children were not only in the image and likeness of God, but also in Adam’s image and likeness, Scripture describes the first three patriarchs, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, all suffering from infertility and famine. All three lived out the twin curses of Adam. Both Abraham and Isaac were driven into another land in order to avoid their respective famines and both publicly repudiated their wives while in this foreign land, acting in the image of their forbear (Gen. 12:10-20, 16:1, 15:21, 26:1-6). Both of Jacob’s wives suffered from infertility (Gen. 30:1, 30:9), while the famine which occurred in the life of Jacob, now named Israel, drove all of Israel’s family into Egypt, where they became enslaved.

Thereafter, the twin curses of famine and infertility weave in and out of the whole long history of Israel’s children. The curses would only be broken by the new Bridegroom, Jesus Christ, through the establishment of a new Tree of Life, the Cross (cf. Acts 10:39, Rev. 22:2). The Church was birthed into existence through the pain of the Cross, with Mary, her face twisted in an agony of sorrow, mirroring the face of her crucified Son: “the woman clothed with the sun . . . cried out in her pangs of birth, in anguish for delivery” (Rev .12:2). At the Cross, the pain of childbirth was taken to its limit and destroyed. Similarly, the Eucharistic prayer of the Mass testifies:

“Blessed are You, Lord, God of all creation. Through Your goodness we have this bread to offer, which earth has given and human hands have made. It will become for us the Bread of Life.

Blessed are You, Lord, God of all creation. Through Your goodness we have this wine to offer, fruit of the vine and work of human hands, it will become our spiritual drink.”

The toil of our hands is united to the work of God’s hands, nailed to the Cross, taken to its limit in death, and also destroyed. Thus, the Bridegroom Jesus Christ, leads His Bride the Church to the Cross, the Tree of Life. Christ smashes through the twin curses, and feeds His Bride with the Fruit of the Tree — His own Body. By thus receiving the Bridegroom into Herself, the Bride who is the Church, along with all of Her members, is made fruitful and is given life as a child of God. The sacrament of the Body and Blood of Christ divinizes us (CCC 460, 1988, 1999), allowing us to partake of the Divine Nature (2 Pet. 1:4).

The sacraments of marriage and the Eucharist are inextricably intertwined. The act of marital union is the created image of the reality of the Eucharist, for after the wedding feast, the bride receives the bridegroom into herself and is made fruitful, and both husband and wife are blessed with new life. As a result, the active attempt to destroy the fruitfulness of the marital act is not only a rejection of the grace of marriage, but it is also the implicit rejection of the sacrament that marriage images, the Eucharist.

Though Huxley, the man whom a contemporary called a “neo-pagan” and who eventually began to dabble with Hinduism, did not consciously understand the theology which lies behind the acts of sexuality and contraception, he instinctively understood their interconnection. Because he wanted his Brave New World society to embrace and live out a contraceptive mentality, it replaces the tree with the industrial complex. Huxley understood that universal sterility is unnatural, and no tree, no living thing could produce it. By removing pregnancy, his worldly society removes the curse of the pain of childbirth. His society further ensures this by populating itself with abortion clinics and factories which bring children into existence through in vitro fertilization, in vitro gestation and cloning. Most women are created sterile, but a few are permitted to retain their fertility so their eggs could be harvested in order to produce the next generation. These women are distinguished by their contraceptive cartridge belts, which they are drilled to use from the time of childhood.

The contraceptive society desires not children, but pleasure. Where there is no desire for children, there is likewise no desire for parents — indeed, the very words “mother” and “father” are curse words, the lowest and most vile form of insult, as the phrases “Mary, our Mother” and “Our Father” are in certain circles today. But a sterile world is impossible to live with on a daily basis. The delight in worldly pleasure leaves an ever-thirsting spiritual desert. His society solves this problem with “soma” — the psychedelic wonder-drug which removes the individual from reality. Still, the use of soma is not enough. People need symbols and liturgy, and Huxley knows it. Fortunately, the Anglican Church left his fictional society a rich legacy. They have the sign of the “T,” a reminder of the first mass-produced item in the world, the Model-T Ford, and not-so- coincidentally a broken echo of the Cross, with its vertical connection to heaven cut off:

“And she had shown Bernard the little golden zipper-fastening in the form of a T which the Arch-Community-Songster of Canterbury had given her as a memento of the weekend she had spent at Lambeth . . . ‘A cardinal,’ Mustapha Mond explained parenthetically, ‘was a kind of Arch-Community Songster.’ ” (pp. 118, 157). Since the Arch-Community Songster is a quasi- cardinal, he also leads a quasi-liturgy. Indeed, Huxley spends over half of chapter five describing the liturgical service in detail, the seating arrangements, the music, the distribution of the soma tablets and the “loving cup” filled with soma drink, during which participants experience “the coming of the Ford.” Indeed, the very name Huxley chose to describe this drug which takes the imbiber out of the world, soma, is nothing more than the Greek word for “body.” In other words, the liturgical service is a parody of the Anglican High Mass, recalling the doctrine of the Real Presence: Body, Blood, Soul and Divinity of Jesus Christ, completely present under either species, an offering of love from God to man. It is not an accident that the “loving” cup is quaffed twelve times, recalling the Christian symbolism for the twelve Apostles and the twelve tribes of Israel. And the result of this quaffing is quite intentionally chosen by Huxley — indeed, it characterizes the effect of the entire contracepting society which the Lambeth conference, led by the Archbishop of Canterbury, helped create:

“The President made another sign of the T and sat down. The service had begun. The dedicated soma tablets were placed in the center of the table. The loving cup of strawberry ice-cream soma was passed from hand to hand and, with the formula, “I drink to my annihilation,” twelve times quaffed. Then to the accompaniment of the synthetic orchestra the First Solidarity Hymn was sung . . .” (p. 53). Huxley builds an anti-Eucharist, a eucharist which appears to give everything, but gives nothing at all. Its final effect is not redemption, divinization, the partaking of the Divine Nature; it is annihilation. In other words, Huxley, neo-pagan, quasi-Hindu mystic that he is, recognizes on an intuitive level that contraception necessarily completes the work of the serpent and original sin. In contraception, Huxley finds the work of the anti-Eucharist, the antichrist.

In less than 180 devastating pages, Aldous Huxley not only tears the mask from the face of contraception, he also provides an excellent proof for the necessity of the papal office. The Anglican Conferences which Huxley so neatly parodied demonstrated that any essentially national church must eventually fall prey to the social pressures they operate within. The Anglican Church, having no leader outside of England, was simply unable to protect itself from the concerns of the country and the people to whom they ministered. The fears sown by the eugenicists and the selfishness of the people were simply too compelling for any religious leader to publicly denounce. Any Church which permitted its doctrines to be socially influenced to this degree would eventually allow their cardinals to become “Arch-Community Songsters.” As it turned out, the papal office alone possessed the strength to protect Christianity from the lies bound up within the grinning death’s heads of the contraceptive mentality and its twin sister, the abortion mill.

Though he saw the intrinsic contradictions inherent in the idea of a “contracepting Christian,” Huxley did not directly ask the question which everyone tempted by contraception must answer.

That question had already been posed in 1880, 50 years earlier, by another of the great authors of literature, Fyodor Dostoevsky. In his masterpiece, The Brothers Karamazov, one of the main characters is being tried for the crime of parricide — murdering his own father. The defense attorney appeals to the jury with a simple, compelling question: “The conventional answer to [the question ‘Who is my father?’] is: ‘He begot you, and you are his flesh and blood, and therefore you are bound to love him.’ The youth involuntarily reflects: ‘But did he love me when he begot me?’ he asks, wondering more and more, ‘Was it for my sake he begot me? He did not know me, not even my sex, at that moment, at the moment of passion, perhaps, inflamed by wine’ ” (p. 397).

“Did he love me when he begot me?” When we actively put up chemical or physical walls between ourselves, our lover, and the child which might be begotten, will we truly have loved that child into existence as God loved us into existence, Who gave Himself totally for us? Are we acting in the image of the living God?

This shortlink

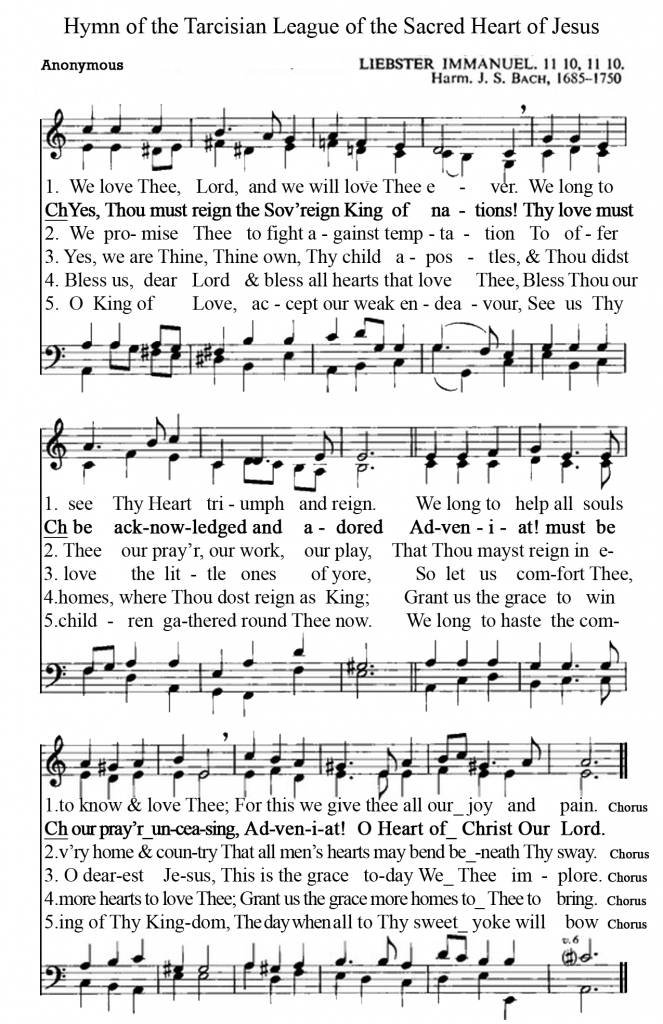

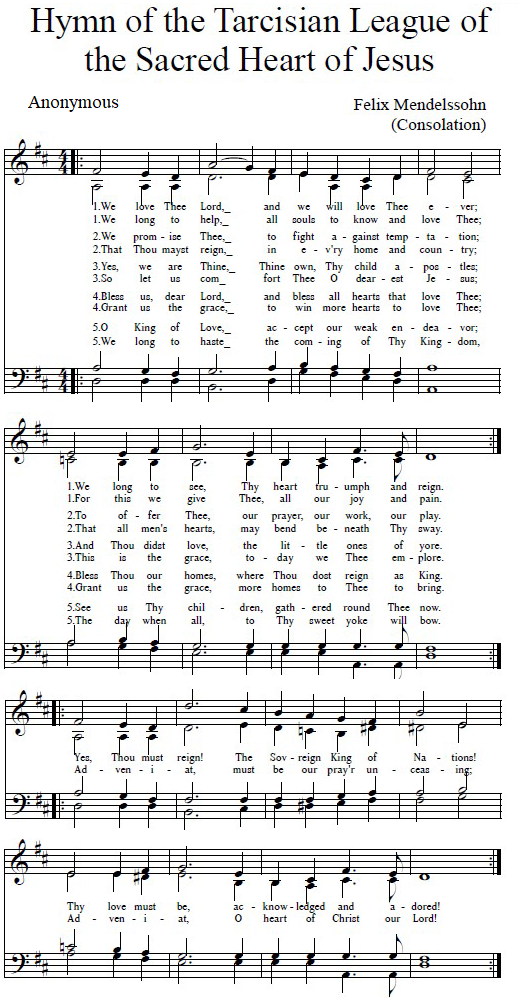

https://www.sing-prayer.org/p/6712

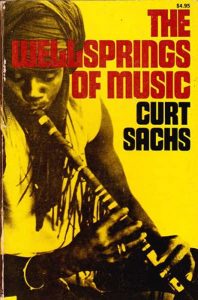

A pioneering student of culture, ethnomusicologist Curt Sachs (1881-1959), made a coherent argument, in terms of the normal coexistence, and, indeed, mutual inter-penetration of cultural influences, among the seeming, disparate forms of fine-art music, authentic folk music, progressive popular music, urban music, and other forms.

A pioneering student of culture, ethnomusicologist Curt Sachs (1881-1959), made a coherent argument, in terms of the normal coexistence, and, indeed, mutual inter-penetration of cultural influences, among the seeming, disparate forms of fine-art music, authentic folk music, progressive popular music, urban music, and other forms.