Why Catholics Must Sing

Family Song-Time vs. Private Phone Music (Ear Buds)

New ideas which you might not previously have encountered

You’re frequently listening to music and being influenced by it. But you were created to make music, to sing it frequently (not necessarily to play a man-made instrument, but to use the God-given musical instrument of your human voice), not merely to consume, commercially or artificially produced music. And if you have ceded direct control of your cultural life, by merely, passively consuming music–without actively producing it with your voice–you run the risk of allowing other, possibly deleterious influences to surreptitiously degrade you in your lifelong quest for virtue.

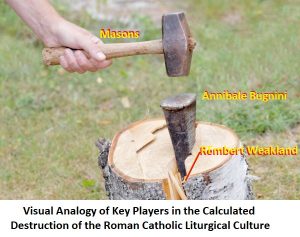

This concept bears upon and is influenced by, the history of the proliferation of the culturally degraded Hootenanny Mass in the mid-1960s. The specifics of this catastrophe were outlined in the account of Msgr. Richard Schuler about the North American, Commission on Sacred Liturgy’s unwanted, unauthorized destructive activity, fomenting cultural revolution in close cooperation with Msgr. Annibale Bugnini.

What were the social and cultural conditions that allowed a dedicated group of modernist liturgical pillagers to attack the Priesthood, the Mass and the Church, degrading the Sacred Liturgy and, along the way, smuggling in an inferior substitute for Sacred Music? It is necessary to move out a little, to envision a higher relationship.

Prior to the rise of the electronic entertainment industry in the 1920s, virtually everyone who was not deaf or tone-deaf, was casually yet intimately involved in singing music, whether in groups or on their own, on a regular basis, in the remotest reaches of their personal lives. (The fact that this cultural background is virtually unknown today, can be attributed to its commonality–everyone knew it at the time, so it would not have been considered remarkable, as it would to those today who don’t know of it.)

But by the time in the 1960s of the intrusion of the new Mass and the introduction of culturally dumbed-down guitar music and inane, non-devotional or catechetical lyrics, most people had already ceased personally singing in their daily lives. Their formerly vigorous, if informal involvement with the musical aspect of culture was reduced to passive consumerism, rendering them vulnerable to consciously planned harm against their religious culture.

A solution, for Traditional Catholics, as they face possible dispersion by wayward higher authority, is to consciously take up the banner of the restoration of Christian culture, especially, in its most everyday forms.

This adverse turn of circumstances, the degradation of cultural life under conditions of poor religious and ethical formation—actually, a vacuum of proper catechesis—necessarily exposed the laity to certain latent, dangerous breakdown-products of a dying culture, to which the musical and poetic arts are inherently at-risk, to which the specialized music of the Church was not immune in a time of the decline of zeal and rise in the desire for accommodating the spirit of the world.

History found in original sources can be condensed into a simple thought-picture of ancient Greek philosophy’s warnings about the dangers of certain scales, rhythms and tempos. These attributes are not abstract technicalities, they are the most immediate, tangible and visceral aspects of music.

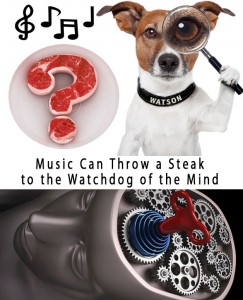

In the most important part of our lives, at Holy Mass and while engaged in personal prayer, we may frequently listen to morally good, sacred music, even Gregorian Plainchant. But that salutary, ethical effect is commonly subverted, in other, less well examined parts of our lives, of only marginally less importance, instead of our choosing to directly, actively sing ethical and culturally full music in our daily activities, as we were created by God to do, whether at prayer, at work or at leisure. In this more private and unheralded part of our lives, we may rather, by privately, passively listening, on the cell-phone or in the car, to less exemplary music, suffer smuggling in truly malevolent influences not so easily detected.

Largely as “consumers” of music, we tend not to make very conscious choices about what we’ve been programmed to think of as “our” preferred musical genres, instead being influenced, against our autonomy by a sector of the cognitive economy called “the manufacture of consent”, so that, without a high level of awareness of the fact, we merely, unconsciously “go with the flow” of background music which we tend to ignore as mere, ambient, mood inducing sound of a neutral, inconsequential character. But our passive, more nearly negligent reception of such programmed culture-substitute, without fostering our own, active participation, can be the vehicle of hidden corruption which affects us directly, irrespective of our lack of awareness of the issue. All the while, we ourselves do not commonly maintain control of our own music lives, failing to directly sing, ethical and culturally full music of our own conscious choice.

“What would you have us do?” Appoint one of your family members, a young person of middle-school age or older, as the family pianist. Institute family song time as a regular part of your week. Or, if it is your preference, learn Irish music; a few children can play instruments, but everyone has fun singing. Using any effective accommodation, develop your family’s cultural acuity–having tremendous fun in the process–in the recovery of Christian culture, and assert your own control over your cultural content.

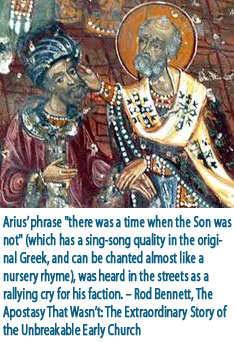

With all the joyous potential of music, it is this vulnerability, the tendency toward cultural passivity, that indisputably dominates the broader, present-day secular culture. And its worst potential bears similarity to an historical precedent, to the contemporary weaponization of degraded culture in the service of disrupting the ancient Latin Mass. This precedent was in the case of the culture war of the ancient Arian heresy, which denied the Divinity of Christ.

Our near-historical ancestors would not have been so easily influenced by the artificial culture-substitute that held sway in the mid-1960s, when the Hootenanny Mass ejected the Church’s ancient, priceless cultural patrimony that had been embraced by many generations of ordinary Catholics. Within the lifetimes of our own great-great-grandparents, people whose names we might know, the majority of music was actively produced by people themselves. This had the effect, that they fully knew the content, and the ethical implications, of music with which they were actively involved. Prior to the intrusion of radio (1923) and sound-cinema ‘talkies’ (1929), there were 300 piano brands in the U.S. alone, and ten × 1 million-selling sheet-music printings per year, with many other songs printed in smaller runs, in the decade leading to the end of the First World War. We need to do some first-person, original, “heavy-lifting” thinking, to realize the implications for the way our culture is exploited, from the fact that “we don’t sing”. We can’t realize what it means, “everyone used to sing”, because by and large, we don’t sing, ever; but everyday singing is culturally normal for the minimal self-realization of Christian culture. Without the direct, kinetic experience of first-person music and the fostering of active, participatory musical experience and memory, our minds can barely register the implications, of an active music life. Click ^ again to contract The social, artistic interaction of singers in an ensemble, even the most informal, contrasts vividly with the current experience of “music” through social media. Harmonic singers must listen closely to each other simultaneous with producing their own vocal output, maintaining their place in the key. (Singers modulate their pitch intricately, based on fundamental acoustic properties of interacting musical tones in triadic harmony, the consonance or dissonance of overtones in the harmonic series between singers’ interacting tones, singers regulating difference-tone beating between pure harmonic consonances and deliberate, mild dissonances.) They concentrate on the implied leader, constantly moderating their volume, tempo and timbre, giving way to an intermittent leader or themselves preparing to take the momentary spotlight. (Singing in multiple, harmony parts creates distinct, expressive head-space niches that individual singers could never occupy when singing in unison.) This constant, dynamic, artistic socialization varies starkly from the social media experience, confined to the sometimes spaghetti-wide aperture into which the internet forces users’ attention. According to John Senior, most people could sing 200 songs. Before radio (1923), if you wanted music, you had to make it yourself . This fundamental fact, sharply divides us from all previous history. People 100 years ago and beyond, frequently sang. People today don’t generally sing, at all.Consider, that broadcast radio began in 1923 and sound-cinema in 1929. Prior to that time, there was vivid interest in music; but while instances of interest in specific songs were sometimes related to musical shows or opera—on the part of those who could afford to attend professional musical performances—most of that enthusiasm was on the part of people themselves singing, in one’s own home and those of friends, at school, in church, in local gathering places like small restaurants and taverns, even in occasional events of local singing clubs or singing-schools, largely music that had become informally traditional, in families, that one learned from one’s parents, relatives and friends. Observe, not the foreground in the video clip, but the background–what’s happening in the parlor, with the people you can hear singing? They are doing what people routinely did, before electronic media began to outsource their direct, authentic practice of culture–they are having a terrific time singing, with their own voices, not being force-fed an artificial, culture-substitute. The stride-style piano in the sound sample, is being played, for fun, by a talented amateur, not being “performed” by a music-school student. The pianist is playing from one of those tens- or hundreds-of-thousands of sheet music printings. But everybody is singing to it. Many singers, for every one pianist playing those thousands of songs. Everyone “knew how” to sing. In their time, and for all previous ages to time immemorial, that was “music”. But is was with the radical distinction from the sense of “music” of our time, that the people themselves were largely the producers, the contemporaneous authors, the active participants in culture, not passive, drooling thralls. “Until the 1920s, the music business was dominated … by song publishers and big vaudeville and theater concerns. … sheet music consistently outsold records of the same hit songs, proving that most of the music heard in homes and in public back then was played by people, not record players. A hit song’s sheet music often sold in the millions between 1910 and 1920. Recorded versions of these songs were at first just seen as a way to promote the sheet music, and were usually released only after sheet music sales began falling.” https://bit.ly/2Obj5gt Between 1900 and 1909, nearly one hundred of the Tin Pan Alley songs had sold more than one million copies of sheet music. https://tinyurl.com/yej3m982It’s true, that music stores featured record displays, but the history is that these were ancillary to sheet music sales—recordings were played to bolster lagging sales of sheet music that was slightly stale, to off-load unsold inventory; otherwise, phono was an expensive novelty, that couldn’t compete with the power of live music, largely self-performed in person based to some degree on fads and fashions set by professional music in theatres and opera houses. But most parlor music publications lacked novelty, it was largely based on the people’s own home cultural heritage, which was traditional. It wouldn’t be until the 1930s and 1940s, when commercial propaganda in movies had managed to portray possession of phono and radio as a luxury, background form of entertainment, that active singing was on its way out. But that was largely an elite phenomenon. Most people sang. In our time, and extending back to the break with active culture during the radio- and talkies-age, we listen to ear-buds, streaming from some website with content from authors from whom we are largely disconnected, probably sponsored, frankly by shadowy social-control groups whose existence we completely fail to suspect, often with a very subtle immorality control agenda completely oblivious to us, appealing to the lowest-base passions to ensure that we don’t cause any trouble resisting the dominant narrative. “Education should aim at destroying free will so that after pupils are thus schooled they will be incapable throughout the rest of their lives of thinking or acting otherwise than as their school masters would have wished…. This subject [totalitarian control of education] will make great strides when it is taken up by scientists under a scientific dictatorship. Anaxagoras maintained that snow is black, but no one believed him. The social psychologists of the future will have a number of classes of school children on whom they will try different methods of producing an unshakable conviction that snow is black. Various results will soon be arrived at. First, that the influence of home is obstructive. Second, that not much can be done unless indoctrination begins before the age of ten. Third, that verses set to music and repeatedly intoned are very effective. Fourth, that the opinion that snow is white must be held to show a morbid taste for eccentricity. …. It is for future scientists to make these maxims precise and discover exactly how much it costs per head to make children believe that snow is black…. Although this science will be diligently studied, it will be rigidly confined to the governing class. The populace will not be allowed to know how its convictions were generated. When the technique has been perfected, every government that has been in charge of education for a generation will be able to control its subjects securely without the need of armies or policemen. — Bertrand Russell, The Impact of Science on Society, 1951 Elderly, bachelor professors were able to get their noses out of a book long enough to sing, rather credibly, in three-part harmony, on the basis of experience with common music education in schools, and of early childhood music practice learned at their mothers’ knees. But, surprise!, virtually everyone could do as well. The gangster is able to assume that the bartender knows how to sing, extemporaneously, the chorus of any one of perhaps 200 random, popular songs. (A murder solved by a song-contest souvenir.) The fault is in wholesale adoption, without taking stock of profound changes to the fundamental way of life, of various technological innovations that disrupt societies and displace personal involvement in culture: the automobile—breaking up families, neighborhoods and societies—, sound-movies, radio and television, causing people to allow technological systems which bypass involvement of the voice, to force-feed them a shabby imitation of culture. That is a lost civilization of music, only 125 years ago–but stretching out into the remotest past of human culture, of all cultures, except ours. Yes, that music was popular—but every parlor music publication had its operatic and church music sections—yes, common culture even with the remote, unlikely potential for inappropriate or immoral lyrics and rhythms. But the fact of the people singing the music themselves, at least afforded them the means of deciding the matter, consciously themselves, rather than allowing unknown programmers to unconsciously influence them for purposes of political and cultural control. Elizabeth Barrett Browning, herself, actually wrote the lyrics. Music lived at home can cease being a revolutionary subversion, and contribute instead to family cohesion and the transmission of one’s own traditions—including the environment of sacred traditions. If we will foster family singing, our children won’t have to be suffering the corrosion of a private music life, quarantined off by ear buds from relationship participation, that degrades their families’ religious, moral and cultural traditions. A practical solution for this issue would be for one of your children to study traditional-popular music for piano, and for your whole family to engage in group singing as an entertainment pastime. It would require the compilation of a kind of musical equivalent to John Senior’s 1,000 good books—the good songs. The Almighty’s acts of performative speech, making creation out of nothing, saying “let there be … and there was”, were once conceived as song; and our inheritance as being made in the image and likeness of God, needs to follow, expressing holy joy in song. JRR Tolkien presents this history using a musical analogy: “God made first the angels, that were the offspring of His thought, and they were with Him before anything else was made. And He spoke to the Angels, propounding to them themes of music; and they sang before Him, and He was glad. But for a long while they sang only each alone, or but few together, while the rest hearkened; for each comprehended only that part of the mind of God from which he came, and in the understanding of their brethren they grew but slowly. … But as the theme progressed, it came into the heart of Satan to interweave matters of his own imagining that were not in accord with the theme of God, for he sought therein to increase the power and glory of the part assigned to himself.” – The Silmarillion. Satan is highly adept at disguising his subversion in music. Only by taking up the reins of our own cultural lives can we deny him this power.

Click ^ again to contract

Past, All Used to Sing

Regarding the assertion that open immorality was not publicly accepted in middle-class culture in the early 20th century: A girl named Rita Antoinette Rizzo was born in 1932 in a working-class Ohio town; she would be known to the world as Mother Anglica, of the EWTN broadcast network. She suffered intense prejudice from children of intact families, with whom she attended school, because, not through her own fault, her parents were divorced. During her young childhood, a controversy arose in public, of the marriage of English King Edward VIII to a divorced woman, Wallis Simpson, and his abdication from the throne. The adverse impact of Mother Angelica’s family situation, growing up under divorce, is negative evidence that, yes, middle-class people could be lacking in sufficient charity. But it also points up to the fact that, apart from popular culture’s near-obsession with defending divorce and re-marriage, even since the life of Lord Horatio Nelson in the early 19th century, when his wife Fanny was vilified in the popular press for seeking reconciliation with her husband after his taking and publicly living with a mistress; at the time of Mother Angelica’s birth, a Catholic-led boycott of Hollywood films which tended to soft pornography, led to the formation of the Hays Code, the prohibition of explicit sexual themes in film and, in general, nudity, and prohibition of adverse depictions in film of Christian ministers. This, then, shows the regard for public morality a century past, for better or for worse, sometimes actually with charity, often with hypocrisy. (In the words of La Rochefoucauld, “hypocrisy is vice’s tribute to virtue.”) But, in principle, open immorality in media and public life, was not generally, socially accepted.