Numerous “hymnals” we access for making arrangements contain not a single note of music—the oldest printed book in North America, the Bay Psalm Book of 1640, is text-only, without any matching tunes. The Hymnal of note-less “hymns” without any reference to applied music was a common category centuries ago. Performing our current task, marrying fitting texts with appropriate, singable tunes, was once commonly understood as a standard practice among organists and choir-directors, without any notice taken as being singular or exceptional; but it is a craft-skill which seems to have fallen out of notice at this time.

An example of a “hymn” unaccompanied by a tune, which can be enhance using this standard method, is the Act of Faith among the fine set of catechetical poems by Fr. Fr. Jeremiah Williams Cummings (1814-1866) from his Songs for Catholic Schools and Aids to Memory for the Catechism (1860).

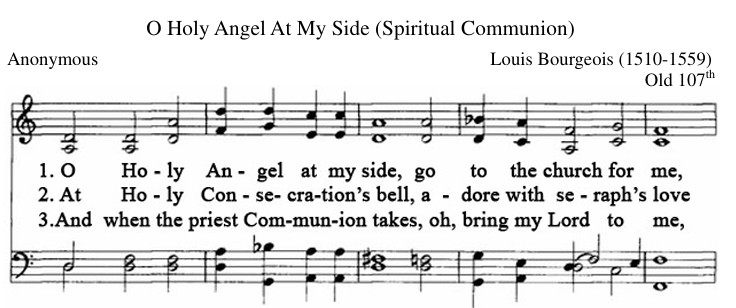

We have another hymn based upon a poem that seems to be in the public domain, having been anonymously attributed to an unknown religious card, but seeming to be unclaimed as to copyright.

The poem, and this website’s rendering of it into music, is titled O Holy Angel at My Side, the lyrics ending with the phrase “the pledge of e’vry grace”.

Here, for this example, we will set it to a tune by the late 16th century, Louis Bourgeois, Old 107th; our work will not only be to set the lyrics in sheet-music, but we will produce a sound file to which the setting can be sung.

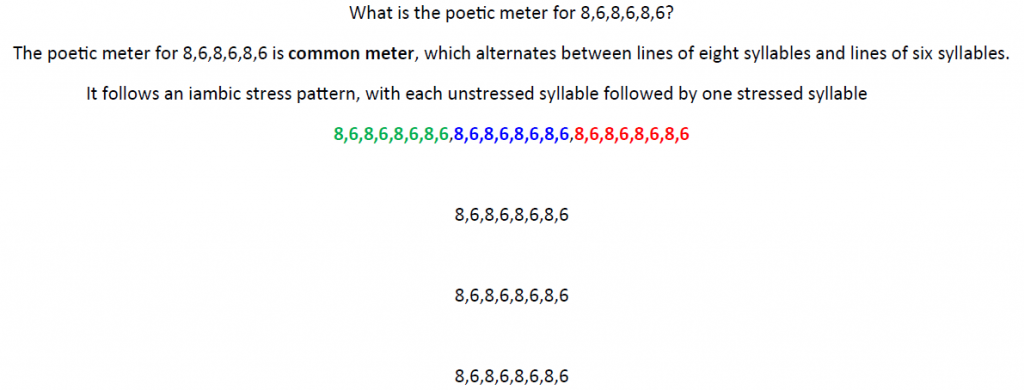

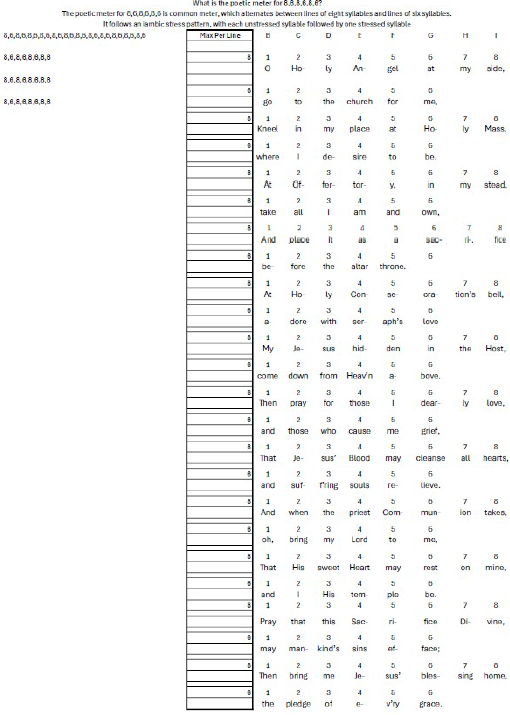

First there is counting work to ascertain if there is a regularly repeating rhythmic pattern, in the poem alone, which is the quality which allows us to meld a poem with a tune.

Both thumbnail images below link to a complete PDF accounting for the full metric of the poem.

After ascertaining the meter in question (the common meter,

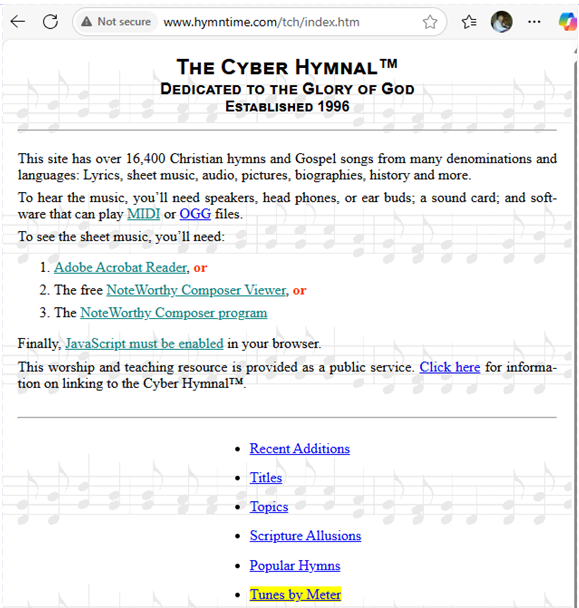

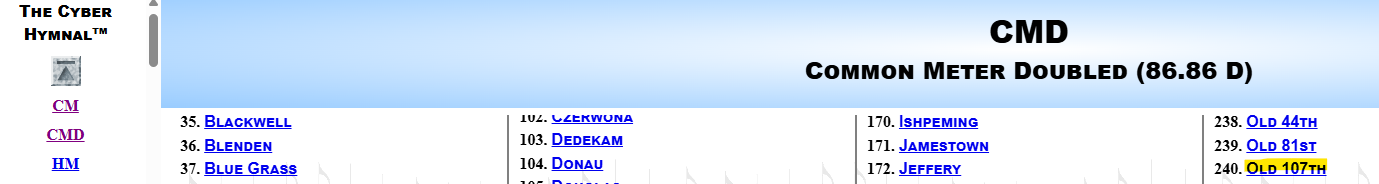

8-6-8-6-8-6-8-6), we find the set of matching tunes on the Cyber Hymnal, the category Tunes by Meter. (I bypassed the Cyber Hymnal host page, jumping directly to the Tunes by Meter page, which is in the old “frames” html system, quite navigable even if it is very obsolescent.)

Here we have to most efficiently find the common meter

8-6-8-6-8-6-8-6. It turns out not to be so complicated, it is the Common Meter Doubled (CMD) at the top of the left sidebar menu.

We have too many choices, greater than 350 for this meter, most of them inappropriate to our purpose, of finding “just the right tune” to complement the purpose of the poetic text, to truly extend it from being a fine poem to being workable music. To manage that load of work, we have to develop a system of quickly and efficiently sampling the great number of sound of files which can be present in each collection of tunes by meter, which are presented to us in the computer format “Musical Instrument Digital Interface” (MIDI)—even though we won’t directly be using MIDI for a final production purpose, we will just be using it as an estimation, a kind of musical thumbnail, to fill-in an approximation of how the ultimately selected tune will work with the text, so that we can set up a framework upon which to finally execute the finished work, words set upon a page of notes, even perhaps to record a sound-sample to which the new pairing (text-to-tune) can be sung.

One simple trick for managing the potentially large number of available tunes, is to use the app named “Casio Music Space” to sample their sound. It has perfectly credible, rudimentary MIDI functionality. |

Or, if you have to get into some big, whiz-bang computer program, you can use something called a “Digital Audio Workstation”, which has MIDI as its native format, its brain impulses.

|

(I’m reverse-engineering here. I have to track down the tune I selected, “Old 107th” by Louis Bourgeois; I really did initially perform this pairing from scratch, using the system described here.)

On the page at the top of the left sidebar menu for CMD (Common Meter Double) I can find my tune, Old 107th. There are greater than 350 tunes on this, rather over-representative page, so it’s necessary to have a very efficient way of downloading, storing, accounting for the names of the tunes, and sampling them—rapidly auditioning them, “naw, naw, naw, HMMM!”.

On the page at the top of the left sidebar menu for CMD (Common Meter Double) I can find my tune, Old 107th. There are greater than 350 tunes on this, rather over-representative page, so it’s necessary to have a very efficient way of downloading, storing, accounting for the names of the tunes, and sampling them—rapidly auditioning them, “naw, naw, naw, HMMM!”.

Among the poems able to be extended with tunes, it is permitted, those that might seem to be very irregular; but they only have to have a repeating metric pattern, however rococo their appearance. A poem by a pre-conversion, John-Henry Newman, he wrote when he was in quarantine from an illness. It was taken up by one of the greatest Protestant hymn composers, John Bachus Dykes. It is carried in the hymnals of all the Protestant denominations, even the Seventh Day Adventists who take strong exception to the Catholic Church—it’s just Catholics who know nothing about it; but despite the very exuberant treatment of it by the Men’s Chorus of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, it is a hymn of repentance, as witnessed by a phrase in the second stanza, “Pride Ruled My Will”.

Now, quite unlike the regularly repeating metric array of the Common Meter, the syllable counts of the poem for Lead Kindly Light (

10-4-10-4-10-10) are, at once, notably irregular, but exactly mirror that meter, however irregular, between each of the 3 verses—meaning, that it was possible for Dykes to set the lyrics in a credible tune, specially crafted for the occasion. This is the criterion necessary for converting from a poem to a tune.

St. John Henry Cardinal Newman’s Hymn of Repentance from Pride

Click the ▶ Button to Hear the Song, or Play the Song in a New Window ⧉

| (10) Lead, kindly Light, amid th’encircling gloom; (4) Lead thou me on! (10) The night is dark, and I am far from home; (4) Lead thou me on! (10) Keep thou my feet; I do not ask to see (10) The distant scene—one step enough for me. |

| (10) I was not ever thus, nor pray’d that thou (4) Shouldst lead me on. (10) I loved to choose and see my path; but now, (4) Lead thou me on! (10) I loved the garish day, and, spite of fears, (10) Pride ruled my will. Remember not past years. |

| (10) So long thy pow’r hath blest me, sure it still (4) Will lead me on (10) O’er moor and fen, o’er crag and torrent, till (4) The night is gone. (10) And with the morn those angel faces smile, (10) Which I have loved long since, and lost awhile! |

So this highly elliptical poem is quite singable as a hymn.

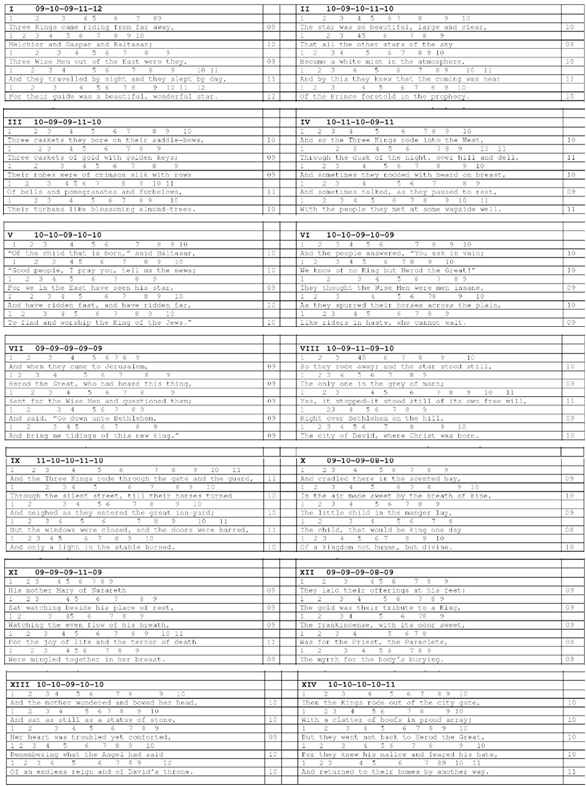

Now there is poem which has other typical characteristics, such as, having repeating rhyming patterns between numbers of lines in the specific verses (1, 3 & 4 rhyme; 2 & 5 rhyme), and regular numbers of lines (5 in all the 14 verses). But it doesn’t have the rhythmically repeating, metric patten which would be expected among the header, summary lines below (Verse I has 09-10-09-11-12, but Verse II asymmetically fails to match, with 10-09-10-11-10, and no metric repetition can be meaningfully be found between any discernable verses among the 14 in the poem), to conventionally allow us to match it to a tune—when enunciating the poem, you can’t “catch the beat” to give the listeners a convincing stomp—although making it a tune has been artificially forced in this instance. (Shakespeare doesn’t typically use rhyming, and Milton seems not to use it at all.)

This is an Epiphany poem, The Three Kings, by the 19th c. American poet William Wadsworth Longfellow (Hiawatha, Evangeline, I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day). It deliberately has that peculiarity, absence of metric symmetry, in common with The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere.

There might be some technical means of accomplishing the task, melding a poem lacking metric symmetry with a tune, but it might not be worth the time.

Click the ▶ Button to Hear the Song, or Play the Song in a New Window ⧉

| Henry Wadsworth Longfellow | Sir John Stainer |

|---|---|

| 1) Three Kings came riding from far away, Melchior and Gaspar and Baltasar; Three Wise Men out of the East were they, And they travelled by night and they slept by day, For their guide was a beautiful, wonderful star. |

2) The star was so beautiful, large and clear, That all the other stars of the sky Became a white mist in the atmosphere, And by this they knew that the coming was near Of the Prince foretold in the prophecy. |

| 3) Three caskets they bore on their saddle-bows, Three caskets of gold with golden keys; Their robes were of crimson silk with rows Of bells, pomegranates and furbelows, Their turbans like blossoming almond-trees. |

4) And so the Three Kings rode into the West, Through the dusk of the night, over hill & dell, & sometimes they nodded with beard on breast, And sometimes talked, as they paused to rest, With the people they met at some wayside well. |

| 5) “Of the child that is born,” said Baltasar, “Good people, I pray you, tell us the news; For we in the East have seen his star, And have ridden fast, and have ridden far, To find and worship the King of the Jews.” |

6) And the people answered, “You ask in vain; We know of no King but Herod the Great!” They thought the Wise Men were men insane, As they spurred their horses across the plain, Like riders in haste, who cannot wait. |

| 7) And when they came to Jerusalem, Herod the Great, who had heard this thing, Sent for the Wise Men and questioned them; And said, “Go down unto Bethlehem, And bring me tidings of this new king.” |

8) So they rode away; and the star stood still, The only one in the grey of morn; Yes, it stopped—it stood still of its own free will, Right over Bethlehem on the hill, The city of David, where Christ was born. |

| 9) And the Three Kings rode through the gate and the guard, Through the silent street, till their horses turned And neighed as they entered the great inn-yard; But the windows were closed, and the doors were barred, And only a light in the stable burned. |

10) And cradled there in the scented hay, In the air made sweet by the breath of kine, The little child in the manger lay, The child, that would be king one day Of a kingdom not human, but divine. |

| 11) His mother Mary of Nazareth Sat watching beside his place of rest, Watching the even flow of his breath, For the joy of life and the terror of death Were mingled together in her breast. |

12) They laid their offerings at his feet: The gold was their tribute to a King, The frankincense, with its odor sweet, Was for the Priest, the Paraclete, The myrrh for the body’s burying. |

| 13) And the mother wondered and bowed her head, And sat as still as a statue of stone, Her heart was troubled yet comforted, Remembering what the Angel had said Of an endless reign and of David’s throne. |

14) Then the Kings rode out of the city gate, With a clatter of hoofs in proud array; But they went not back to Herod the Great, For they knew his malice and feared his hate, And returned to their homes by another way. |