Why Catholics Must Sing

Family Song-Time vs. Private Phone Music (Ear Buds)

New ideas which you might not previously have encountered.

You’re frequently listening to music and being influenced by it. But you were created to make music, to sing it frequently, everywhere, not just in Church—not necessarily to play a man-made instrument, but to use the God-given musical instrument of your own human voice—not merely to consume, commercially or artificially produced music. And if you have ceded direct control of your cultural life, by merely, passively consuming music–without actively producing it with your voice–you run the risk of allowing other, possibly deleterious influences to surreptitiously divert you in your lifelong quest for virtue.

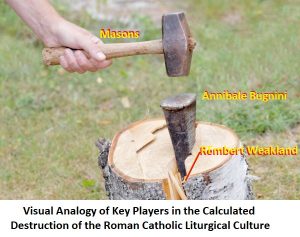

This concept bears upon and is influenced by, the history of the proliferation of the culturally degraded Hootenanny Mass in the mid-1960s. The specifics of this catastrophe were outlined in the account of Msgr. Richard Schuler about the North American, Commission on Sacred Liturgy’s unwanted, unauthorized destructive activity, fomenting cultural revolution in close cooperation with Msgr. Annibale Bugnini.

https://www.fisheaters.com/frsomerville.html

Fr. Sommerville composed a number of musically and devotionally excellent hymns carried in The Traditional Roman Hymnal.

Dear Fellow Catholics in the Roman Rite,

1 – I am a priest who for over ten years collaborated in a work that became a notable harm to the Catholic Faith. I wish now to apologize before God and the Church and to renounce decisively my personal sharing in that damaging project. I am speaking of the official work of translating the new post-Vatican II Latin liturgy into the English language, when I was a member of the Advisory Board of the International Commission on English Liturgy (I.C.E.L.).

2 – I am a priest of the Archdiocese of Toronto, Canada, ordained in 1956. Fascinated by the Liturgy from early youth, I was singled out in 1964 to represent Canada on the newly constituted I.C.E.L. as a member of the Advisory Board. At 33 its youngest member, and awkwardly aware of my shortcomings in liturgiology and related disciplines, I soon felt perplexity before the bold mistranslations confidently proposed and pressed by the everstrengthening radical/progressive element in our group. I felt but could not articulate the wrongness of so many of our committee’s renderings.

3 – Let me illustrate briefly with a few examples. To the frequent greeting by the priest, The Lord be with you, the people traditionally answered, and with your (Thy) spirit: in Latin, Et cum spiritu tuo. But I.C.E.L. rewrote the answer: And also with you. This, besides having an overall trite sound, has added a redundant word, also. Worse, it has suppressed the word spirit which reminds us that we human beings have a spiritual soul. Furthermore, it has stopped the echo of four (inspired) uses of with your spirit in St. Paul’s letters.

4 – In the I confess of the penitential rite, I.C.E.L. eliminated the threefold through my fault, through my fault, through my most grievous fault, and substituted one feeble through my own fault. This is another nail in the coffin of the sense of sin.

5 – Before Communion, we pray Lord I am not worthy that thou shouldst (you should) enter under my roof. I.C.E.L. changed this to … not worthy to receive you. We loose the roof metaphor, clear echo of the Gospel (Matth. 8:8), and a vivid, concrete image for a child.

6 – I.C.E.L.’s changes amounted to true devastation especially in the oration prayers of the Mass. The Collect or Opening Prayer for Ordinary Sunday 21 will exemplify the damage. The Latin prayer, strictly translated, runs thus: O God, who make the minds of the faithful to be of one will, grant to your peoples (grace) to love that which you command and to desire that which you promise, so that, amidst worldly variety, our hearts may there be fixed where true joys are found.

7 – Here is the I.C.E.L. version, in use since 1973: Father, help us to seek the values that will bring us lasting joy in this changing world. In our desire for what you promise, make us one in mind and heart.

8 – Now a few comments: To call God Father is not customary in the Liturgy, except Our Father in the Lord’s prayer. Help us to seek implies that we could do this alone (Pelagian heresy) but would like some aid from God. Jesus teaches, without Me you can do nothing. The Latin prays grant (to us), not just help us. I.C.E.L.’s values suggests that secular buzzword, “values” that are currently popular, or politically correct, or changing from person to person, place to place. Lasting joy in this changing world, is impossible. In our desire presumes we already have the desire, but the Latin humbly prays for this. What you promise omits “what you (God) command”, thus weakening our sense of duty. Make us one in mind (and heart) is a new sentence, and appears as the main petition, yet not in coherence with what went before. The Latin rather teaches that uniting our minds is a constant work of God, to be achieved by our pondering his commandments and promises. Clearly, I.C.E.L. has written a new prayer. Does all this criticism matter? Profoundly! The Liturgy is our law of praying (lex orandi), and it forms our law of believing (lex credendi). If I.C.E.L. has changed our liturgy, it will change our faith. We see signs of this change and loss of faith all around us.

9 – The foregoing instances of weakening the Latin Catholic Liturgy prayers must suffice. There are certainly THOUSANDS OF MISTRANSLATIONS in the accumulated work of I.C.E.L. As the work progressed I became a more and more articulate critic. My term of office on the Advisory Board ended voluntarily about 1973, and I was named Member Emeritus and Consultant. As of this writing I renounce any lingering reality of this status.

10 – The I.C.E.L. labours were far from being all negative. I remember with appreciation the rich brotherly sharing, the growing fund of church knowledge, the Catholic presence in Rome and London and elswhere, the assisting at a day-session of Vatican II Council, the encounters with distinguished Christian personalities, and more besides. I gratefully acknowledge two fellow members of I.C.E.L. who saw then, so much more clearly than I, the right translating way to follow: the late Professor Herbert Finberg, and Fr. James Quinn S.J. of Edinburgh. Not for these positive features and persons do I renounce my I.C.E.L. past, but for the corrosion of Catholic Faith and of reverence to which I.C.E.L.’s work has contributed. And for this corrosion, however slight my personal part in it, I humbly and sincerely apologize to God and to Holy Church.

11 – Having just mentioned in passing the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), I now come to identify my other reason for renouncing my translating work on I.C.E.L. It is an even more serious and delicate matter. In the past year (from mid 2001), I have come to know with respect and admiration many traditional Catholics. These, being persons who have decided to return to pre-Vatican II Catholic Mass and Liturgy, and being distinct from “conservative” Catholics (those trying to retouch and improve the Novus Ordo Mass and Sacraments of post-Vatican II), these Traditionals, I say, have taught me a grave lesson. They brought to me a large number of published books and essays. These demonstrated cumulatively, in both scholarly and popular fashion, that the Second Vatican Council was early commandeered and manipulated and infected by modernist, liberalist, and protestantizing persons and ideas. These writings show further that the new liturgy produced by the Vatican “Concilium” group, under the late Archbishop A. Bugnini, was similarly infected. Especially the New Mass is problematic. It waters down the doctrine that the Eucharist is a true Sacrifice, not just a memorial. It weakens the truth of the Real Presence of Christ’s victim Body and Blood by demoting the Tabernacle to a corner, by reduced signs of reverence around the Consecration, by giving Communion in the hand, often of women, by cheapering the sacred vessels, by having used six Protestant experts (who disbelieve the Real Presence) in the preparation of the new rite, by encouraging the use of sacro-pop music with guitars, instead of Gregorian chant, and by still further novelties.

12 – Such a litany of defects suggests that many modern Masses are sacrilegious, and some could well be invalid. They certainly are less Catholic, and less apt to sustain Catholic Faith.

13 – Who are the authors of these published critiques of the Conciliar Church? Of the many names, let a few be noted as articulate, sober evaluators of the Council: Atila Sinka Guimaeres (In the Murky Waters of Vatican II), Romano Amerio (Iota Unum: A Study of the Changes in the Catholic Church in the 20th Century), Michael Davies (various books and booklets, TAN Books), and Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, one the Council Fathers, who worked on the preparatory schemas for discussions, and has written many readable essays on Council and Mass (cf Angelus Press).

14 – Among traditional Catholics, the late Archbishop Lefebvre stands out because he founded the Society of St Pius X (SSPX), a strong society of priests (including six seminaries to date) for the celebration of the traditional Catholic liturgy. Many Catholics who are aware of this may share the opinion that he was excommunicated and that his followers are in schism. There are however solid authorities (including Cardinal Ratzinger, the top theologian in the Vatican) who hold that this is not so. SSPX declares itself fully Roman Catholic, recognizing Pope John Paul II while respectfully maintaining certain serious reservations.

15 – I thank the kindly reader for persevering with me thus far. Let it be clear that it is FOR THE FAITH that I am renouncing my association with I.C.E.L. and the changes in the Liturgy. It is FOR THE FAITH that one must recover Catholic liturgical tradition. It is not a matter of mere nostalgia or recoiling before bad taste.

16 – Dear non-traditional Catholic Reader, do not lightly put aside this letter. It is addressed to you, who must know that only the true Faith can save you, that eternal salvation depends on holy and grace- filled sacraments as preserved under Christ by His faithful Church. Pursue these grave questions with prayer and by serious reading, especially in the publications of the Society of St Pius X.

17 – Peace be with you. May Jesus and Mary grant to us all a Blessed Return and a Faithful Perseverance in our true Catholic home.

Rev Father Stephen F. Somerville, STL. (April 1, 1931 – December 12, 2015)

What were the social and cultural conditions that allowed a dedicated group of modernist liturgical pillagers to attack the Priesthood, the Mass and the Church, degrading the Sacred Liturgy and, along the way, smuggling in an inferior substitute for Sacred Music?

It is necessary to move out a little, to envision a higher relationship.

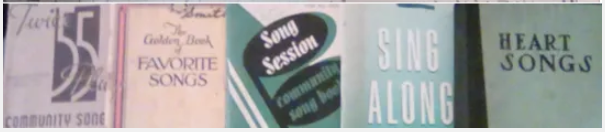

Prior to the rise of the electronic entertainment industry in the 1920s, virtually everyone who was not deaf or tone-deaf, was casually yet intimately involved in singing music, whether in groups or on their own, on a regular basis, in the remotest reaches of their personal lives. (The fact that this cultural background is virtually unknown today, can be attributed to its commonality–everyone knew it at the time, so it would not have been considered remarkable, as it would to those today who don’t know of it.)

But by the time in the 1960s of the intrusion of the new Mass and the introduction of culturally dumbed-down guitar music and inane, non-devotional or catechetical lyrics, most people had already ceased personally singing in their daily lives. Their formerly vigorous, if informal involvement with the musical aspect of culture was reduced to passive consumerism, rendering them vulnerable to consciously planned harm against their religious culture.

A solution, for Traditional Catholics, as they face possible dispersion by wayward higher authority, is to consciously take up the banner of the restoration of Christian culture, especially, in its most everyday forms.

This adverse turn of circumstances, the degradation of cultural life under conditions of poor religious and ethical formation—actually, a vacuum of proper catechesis—necessarily exposed the laity to certain ambient, dangerous, latent breakdown-products of a dying culture, to which the musical and poetic arts are inherently at-risk, to which the specialized music of the Church was not immune in a time of the decline of zeal and rise in the desire for accommodating the spirit of the world, termed at the time of the Council aggorniamento, “bringing up to date”.

History found in original sources can be condensed into a simple thought-picture of ancient Greek philosophy’s warnings about the dangers of certain scales, rhythms and tempos. These attributes are not abstract technicalities, they are the most immediate, tangible and visceral aspects of music.

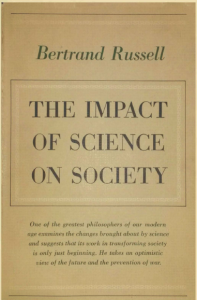

“Education should aim at destroying free will so that after pupils are thus schooled they will be incapable throughout the rest of their lives of thinking or acting otherwise than as their school masters would have wished…. This subject [totalitarian control of education] will make great strides when it is taken up by scientists under a scientific dictatorship. Anaxagoras maintained that snow is black, but no one believed him. The social psychologists of the future will have a number of classes of school children on whom they will try different methods of producing an unshakable conviction that snow is black. Various results will soon be arrived at. First, that the influence of home is obstructive. Second, that not much can be done unless indoctrination begins before the age of ten. Third, that verses set to music and repeatedly intoned are very effective. Fourth, that the opinion that snow is white must be held to show a morbid taste for eccentricity. …. It is for future scientists to make these maxims precise and discover exactly how much it costs per head to make children believe that snow is black…. Although this science will be diligently studied, it will be rigidly confined to the governing class. The populace will not be allowed to know how its convictions were generated. When the technique has been perfected, every government that has been in charge of education for a generation will be able to control its subjects securely without the need of armies or policemen. — Bertrand Russell, The Impact of Science on Society, 1951

In the most important part of our lives, at Holy Mass and while engaged in personal prayer, we may frequently listen to morally good, sacred music, even Gregorian Plainchant. But that salutary, ethical effect is commonly subverted, in other, less well examined parts of our lives, of only marginally less importance, instead of our choosing to directly, actively sing ethical and culturally full music in our daily activities, as we were created by God to do, whether at prayer, at work or at leisure. In this more private and unheralded part of our lives, we may rather, by privately, passively listening, on the cell-phone or in the car, to less exemplary music, suffer smuggling in truly malevolent influences not so easily detected.

Largely as “consumers” of music, we tend not to make very conscious choices about what we’ve been programmed to think of as “our” preferred musical genres, instead being influenced, against our autonomy by a sector of the cognitive economy called “the manufacture of consent”, so that, without a high level of awareness of the fact, we merely, unconsciously “go with the flow” of background music which we tend to ignore as mere, ambient, mood inducing sound of a neutral, inconsequential character. But our passive, more nearly negligent reception of such programmed culture-substitute, without fostering our own, active participation, can be the vehicle of hidden corruption which affects us directly, irrespective of our lack of awareness of the issue. All the while, we ourselves do not commonly maintain control of our own music lives, failing to directly sing, ethical and culturally full music of our own conscious choice.

“What would you have us do?” Appoint one of your family members, a young person of middle-school age or older, as the family pianist. Institute family song time as a regular part of your week. Or, if it is your preference, learn Irish music; a few children can play instruments, but everyone has fun singing. Using any effective accommodation, develop your family’s cultural acuity–having tremendous fun in the process–in the recovery of Christian culture, and assert your own control over your cultural content.

With all the joyous potential of music, it is this vulnerability, the tendency toward cultural passivity, that indisputably dominates the broader, present-day secular culture. And its worst potential bears similarity to an historical precedent, to the contemporary weaponization of degraded culture in the service of disrupting the ancient Latin Mass. This precedent was in the case of the centuries-long culture war against Christendom by the ancient Arian heresy, which denied the Divinity of Christ.

Our near-historical ancestors would not have been so easily influenced by the artificial culture-substitute that held sway in the mid-1960s, when the Hootenanny Mass ejected the Church’s ancient, priceless cultural patrimony that had been embraced by many generations of ordinary Catholics. Within the lifetimes of our own great-great-grandparents, people whose names we might know, the majority of music was actively produced by people themselves. This had the effect, that they fully knew the content, and the ethical implications, of music with which they were actively involved. Prior to the intrusion of radio (1923) and sound-cinema ‘talkies’ (1929), there were 300 piano brands in the U.S. alone —the piano is much easier to play well than the guitar— and ten × 1 million-selling sheet-music printings per year, with many other songs printed in smaller runs, in the decade leading to the end of the First World War. We need to do some first-person, original, “heavy-lifting” thinking, to realize the implications for the way our culture is exploited, from the fact that “we don’t sing”. We have difficulty realizing what it actually means, “everyone used to sing”, because by and large, we don’t sing, at all, ever; but everyday singing is culturally normal for the minimal self-realization of Christian culture. Without the direct, kinetic experience of first-person music and the fostering of active, participatory musical experience and memory, our minds can barely register the implications, of an active music life. Click ^ again to contract The social, artistic interaction of singers in an ensemble, even the most informal, contrasts vividly with the current, isolated experience of “music” through “social” media. Harmonic singers relating directly with one another, must listen closely among themselves, simultaneous with producing their own vocal output, listening to themselves relative to others, maintaining their place in the key. (Singers modulate their pitch intricately, based on fundamental acoustic properties of interacting musical tones in triadic harmony, the consonance or dissonance of overtones in the harmonic series between singers’ interacting tones, singers regulating difference-tone beating between pure harmonic consonances and deliberate, mild dissonances.) They concentrate on the implied leader, constantly moderating their volume, tempo and timbre, giving way to an intermittent leader or themselves preparing to take the momentary spotlight. (Singing in multiple, harmony parts creates distinct, expressive head-space niches that individual singers could never occupy when singing in unison.) This constant, dynamic, artistic socialization varies starkly from the social media experience, confined to the sometimes spaghetti-wide aperture into which the internet forces users’ attention. According to John Senior, most people could sing 200 songs. Before radio (1923), if you wanted music, you had to make it yourself . This fundamental fact, sharply divides us from all previous history. People 100 years ago and beyond, frequently sang. People today don’t generally sing, at all.Consider, that broadcast radio began in 1923 and sound-cinema in 1929. Prior to that time, there was vivid interest in music; but while instances of concern for specific songs were sometimes related to musical shows or opera—on the part of those who could afford to attend professional musical performances—most of that enthusiasm was on the part of people themselves singing, in one’s own home and those of friends, at school, in church, in local gathering places like small restaurants and taverns, even in occasional events of local singing clubs or singing-schools, largely music that had gradually become informally traditional, not fly-by-night novelty songs, in families, that one learned from one’s parents, relatives and friends. Observe, not the foreground in the video clip, but the background–what’s happening in the parlor, with the people you can hear singing? They are doing what people routinely did, before electronic media began to outsource their direct, authentic practice of culture–they are having a terrific time singing, with their own voices, not being force-fed an artificial, culture-substitute. The stride-style piano in the sound sample, is being played, for fun, by a talented amateur, not being “performed” by a music-school student. The pianist is playing from one of those tens- or hundreds-of-thousands of sheet music printings. But everybody is singing to it. Many singers, for every one pianist playing those thousands of songs. Everyone “knew how” to sing. A number of film archive-vault re-presentations of silent “flickers”, work well without a score—prior to sound-cinema, the “visual-stream” was largely independent from the background music; multiple music scores can be fitted to individual silent films. But without a good silent-film, music score—even one largely improvised—silent films would be unlikely to succed. “Magic Lantern” slideshow presentations, a very popular form of media prior to the proliferation of silent film, could easily be played without any score, especially in homes; but in public exhibitions, the inclusion of background music would have been the rule—possibly a majority of which was improvised. The Prominent Role of Music, Even After the Proliferation of Sound Cinema Europe-trained film composer Miklos Rozsa was brought in to save the film production from what amounted to disaster, with the application of a professional music score in the light-classic genre that would accord with the expectations of audiences of that day. After Rozsa’s intervention, “The Lost Weekend” went on receive seven Academy Award nominations and to win four – including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Actor – as well as the first Cannes Film Festival Grand Prix. The overwhelming primacy of the element of music in cinema—rather than a fluke, the dominance of music in cinema is the norm—in terms of setting the emotional tone, to reverse the normal precedence, almost as if the visual component of cinema is secondary accompaniment to primacy of the music score. This is shown by the career history of the dean of golden-age Hollywood film composers, Max Steiner. Brought in to salvage King Kong (1933), a film that was likely to fail until he was engaged to supply the music, Steiner led Kong on to garner worldwide rentals of nearly $3 million and profits of $1.3 million (the equivalent of $18 million today) at a time when it cost 25¢ to go to the movies, a successful run for the time. For the 1939 Gone With the Wind, Steiner defied David O. Selznick’s direction to use existing classical music, independently composing more than 3 hours of original film music and hiring an 80-piece orchestra on his own recognizance. (No other division of the film production process would have ever enjoyed such independence from the normal budgetary oversight obligatory upon all production divisions.) Steiner went on to win the Academy Award for Best Music, Original Score, one of 10 Oscars garnered by Gone With the Wind. Counterintuitively, it might be argued that the single most important member of a motion picture’s creative team is not, the lead actor, the script playwright, the producer or the director –but, rather the, film score composer. In their time, and for all previous ages to time immemorial, first-person participation was “music”. But it was with the radical distinction from the sense of “music” of our time, that the people themselves were largely the producers, the contemporaneous authors, the active participants in culture, not passive, drooling thralls. “Until the 1920s, the music business was dominated … by song publishers and big vaudeville and theater concerns. … sheet music consistently outsold records of the same hit songs, proving that most of the music heard in homes and in public back then was played by people, not record players. A hit song’s sheet music often sold in the millions between 1910 and 1920. Recorded versions of these songs were at first just seen as a way to promote the sheet music, and were usually released only after sheet music sales began falling.” —History of the Record Industry, 1920— 1950s Between 1900 and 1909, nearly one hundred of the Tin Pan Alley songs had sold more than one million copies of sheet music. —Encyclopedia.com–1900s-musicIt’s true, that music stores featured record displays, but the history is that these were ancillary to sheet music sales—recordings were played to bolster lagging sales of sheet music that was slightly stale, to off-load unsold inventory; featured sheet-music offerings would be demonstrated by pianists employed by music stores, for those who weren’t that facile at sight-reading; otherwise, phono was an expensive novelty, that couldn’t compete with the power of live music, largely self-performed in person based to some degree on fads and fashions set by professional music in theatres and opera houses. But most parlor music publications lacked novelty, the songs they contained were largely based on the people’s own home cultural heritage, which was traditional. It wouldn’t be until the 1930s and 1940s, when commercial propaganda in movies had managed to portray possession of phono and radio as a luxury, background form of entertainment to be aspired for possession, that active singing was on its way out. But that was largely an elite phenomenon. Most people sang. Elderly, bachelor professors were able to get their noses out of a book long enough to sing, rather credibly, in three-part harmony, on the basis of experience with common music education in schools, and of early childhood music practice learned at their mothers’ knees. But, surprise!, virtually everyone could do as well. There was a music television show, Sing Along with Mitch, led by chorus director Mitch Miller, that ran from 1961 to 1964. Its nostalgia for the common music life 50 years prior would be ridiculed today. But there had been a time, prior to the development of talkies and radio, when common people genuinely loved just singing along. The following clip gives a sense of that cultural milieu. The gangster is able to assume that the bartender knows how to sing, extemporaneously, the chorus of any one of perhaps 200 random, popular songs. (A murder solved by a song-contest souvenir.) The fault is in wholesale adoption, without taking stock of profound changes to the fundamental way of life, of various technological innovations that disrupt societies and displace personal involvement in culture: the automobile—breaking up families, neighborhoods and societies—, sound-movies, radio and television, causing people to allow technological systems which bypass involvement of the voice, to force-feed them a shabby imitation of culture. That is a lost civilization of music, only 125 years ago–but stretching out into the remotest past of human culture, of all cultures, except ours. Yes, that music was popular—but every parlor music publication had its operatic and church music sections—yes, common culture even with the remote, unlikely potential for inappropriate or immoral lyrics and rhythms. But the fact of the people singing the music themselves, at least afforded them the means of deciding the matter, consciously themselves, rather than allowing unknown programmers to unconsciously influence them for purposes of political and cultural control. Elizabeth Barrett Browning, herself, actually wrote the lyrics. Wilt thou have my hand to lie along with thine? Music lived at home can cease being a revolutionary subversion, and contribute instead to family cohesion and the transmission of one’s own traditions—including the environment of sacred traditions. If we will foster family singing, our children won’t have to be suffering the corrosion of a private music life, quarantined off by ear buds from relationship participation, that degrades their families’ religious, moral and cultural traditions. It would require the compilation of a kind of musical equivalent to John Senior’s 1,000 good books– The Almighty’s acts of performative speech, making creation out of nothing, saying “let there be … and there was”, were once conceived as song; and our inheritance as being made in the image and likeness of God, needs to follow, expressing holy joy in song. JRR Tolkien presents this history using a musical analogy: “God made first the angels, that were the offspring of His thought, and they were with Him before anything else was made. And He spoke to the Angels, propounding to them themes of music; and they sang before Him, and He was glad. But for a long while they sang only each alone, or but few together, while the rest hearkened; for each comprehended only that part of the mind of God from which he came, and in the understanding of their brethren they grew but slowly. … But as the theme progressed, it came into the heart of Satan to interweave matters of his own imagining that were not in accord with the theme of God, for he sought therein to increase the power and glory of the part assigned to himself.” – The Silmarillion. Satan is highly adept at disguising his subversion in music. Only by taking up the reins of our own cultural lives can we deny him this power.

Click ^ again to contract

Test audiences laughed at what should have been a highly dramatic moment in The Lost Weekend (1945), during protagonist Ray Milland’s suicide-attempt scene, in which Jane Wyman wrestled him for a gun. (In the aftermath of the repeal of Prohibition, a decade after William Powell and Myrna Loy, as “Nick and Nora” in Dashiell Hammett’s The Thin Man (1934) had made excessive alcohol-consumption an object of humor verging into the ridiculous, new ground was broken by The Lost Weekend in seriously addressing the topic of alcoholism.) Once the dramatic production was nearing completion, at test audience showings immediately preceding final editing, the last thing producers wanted was for people to be laughing at one of the film’s crisis scenes.

Test audiences laughed at what should have been a highly dramatic moment in The Lost Weekend (1945), during protagonist Ray Milland’s suicide-attempt scene, in which Jane Wyman wrestled him for a gun. (In the aftermath of the repeal of Prohibition, a decade after William Powell and Myrna Loy, as “Nick and Nora” in Dashiell Hammett’s The Thin Man (1934) had made excessive alcohol-consumption an object of humor verging into the ridiculous, new ground was broken by The Lost Weekend in seriously addressing the topic of alcoholism.) Once the dramatic production was nearing completion, at test audience showings immediately preceding final editing, the last thing producers wanted was for people to be laughing at one of the film’s crisis scenes.

Regarding the assertion that open immorality was not publicly accepted in middle-class culture in the early 20th century: A girl named Rita Antoinette Rizzo was born in 1932 in a working-class Ohio town; she would come to be known to the world as Mother Anglica, of the EWTN broadcast network. She suffered intense prejudice from children of intact families, with whom she attended school, because, not through her own fault, her parents were divorced. During her young childhood, a controversy arose in public, of the marriage of English King Edward VIII to a divorced woman, Wallis Simpson, and his abdication from the throne. The adverse impact of Mother Angelica’s family situation, growing up under divorce, is negative evidence that, yes, middle-class people could be lacking in sufficient charity. But it also points up to the fact that, apart from popular culture’s near-obsession with defending divorce and re-marriage, even since the life of Lord Horatio Nelson in the early 19th century, when his wife Fanny was vilified in the popular press for seeking reconciliation with her husband after his taking and publicly living with a mistress; at the time of Mother Angelica’s birth, a Catholic-led boycott of Hollywood films which tended to soft pornography, led to the formation of the Hays Code, the prohibition of explicit sexual themes in film and, in general, nudity, and prohibition of adverse depictions in film of Christian ministers. This, then, shows the regard for public morality a century past, for better or for worse, sometimes actually with charity, often with hypocrisy. (In the words of La Rochefoucauld, “hypocrisy is vice’s tribute to virtue.”) But, in principle, open immorality in media and public life, was not generally, socially accepted.

To lie along with thine?

As a little stone in a running stream,

it seems to lie and pine.

Now drop the poor pale hand, Dear,

unfit to plight with thine.

Wilt thou have my hand to lie along with thine?

To lie along with thine?

A practical solution for this issue would be for one of your children to study traditional-popular music for piano, and for your whole family to engage in group singing as an entertainment pastime.